During our 2023'a Celebrate Waters evening, CELP proudly presented Carla Carlson, retired Muckleshoot Analyst/Hydrologist with…

Thank You for a Wonderful Celebrate Waters 2022

Thank you to everyone who came out for our 2022 Celebrate Waters event on September 15th! It was a lively evening filled with engaging conversation, catching up with friends and colleagues, an illuminating keynote presentation, and granted us all the honor of recognizing this year’s Water Hero, Daryl Williams.

In his keynote presentation—David Troutt, Natural Resources Director for the Nisqually Indian Tribe—spoke about the Nisqually Community Forest and the tribe’s leadership in sustainable forest management.

Some of the best timberlands in the country are found in the Nisqually River Watershed. Combined with the superb growing conditions, uniquely low tax rates, existing infrastructure, and direct access to shipping ports, the Nisqually gained notice of investors all over the world who have been buying up and cutting down forests for significant profit. Currently, over 100,000 acres—nearly 25 percent of the watershed’s total land mass—are privately held commercial timberlands. But until recently, none of those investors were members of the local Nisqually Watershed community itself. So in 2010, concerned about the ecological and economic impacts of intensifying timber harvest, a diverse group of Nisqually stakeholders came together to develop a shared vision for the future of commercial forestry in the watershed—one built around local ownership and management.

In doing so, they stumbled across a concept that was centuries old on the East Coast, but brand new to the PNW: ‘community forestry’. Creating an ambitious plan to build a community owned and managed forest—the success of which will not only be measured by lumber production and local economic benefit, but also by how well it improves and protects fish and wildlife habitat, and provides recreational and educational opportunities—they got to work.

In 2014, the Nisqually Community Forest was incorporated as a 501(c)(3) nonprofit conservancy organization and a wholly-owned subsidiary of the Nisqually Land Trust with the power to buy, sell, hold, and manage working timberlands. Currently, the Nisqually Community Forest is 4,120 acres, the largest nonprofit community forest in the PNW.

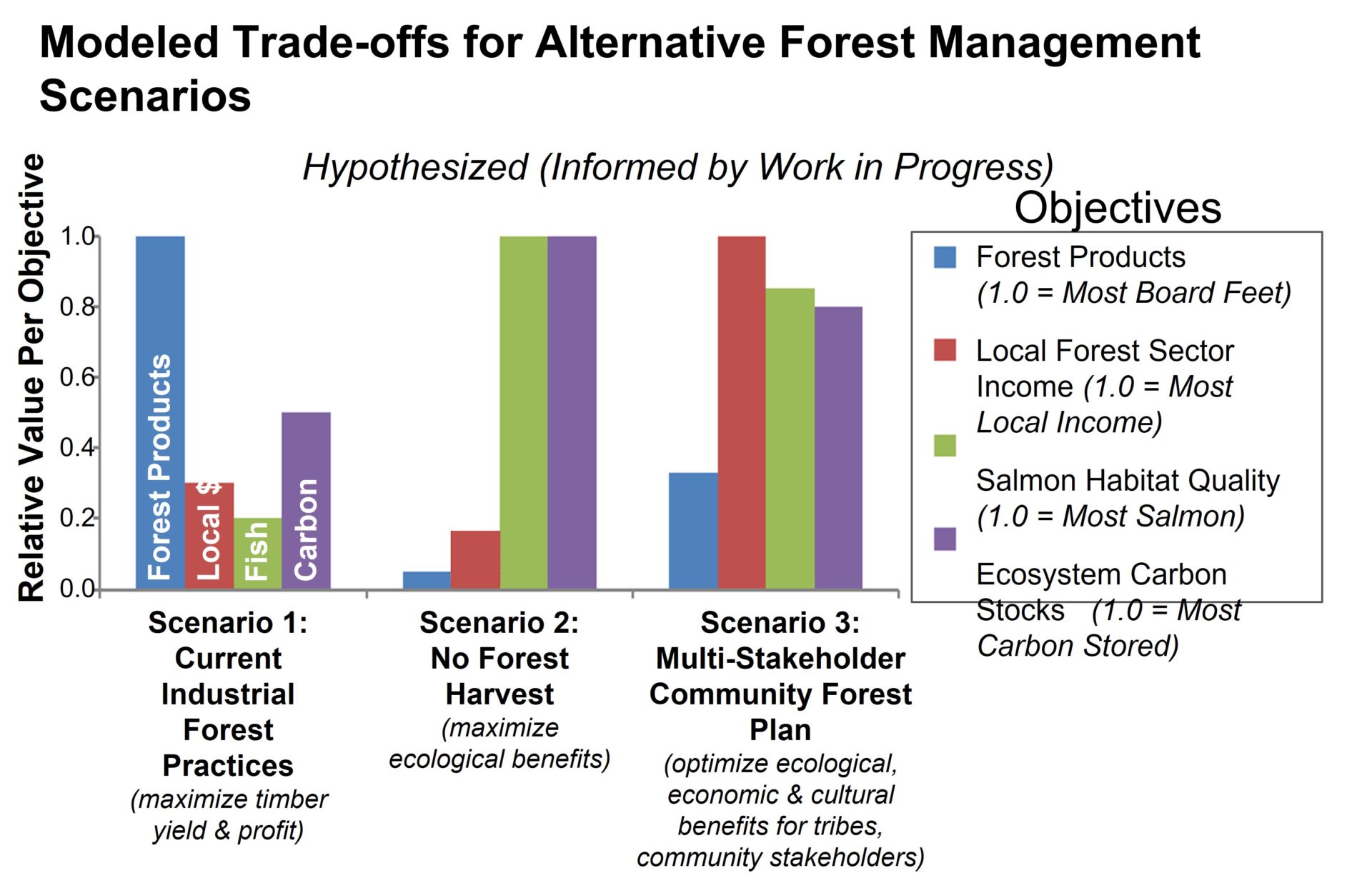

So how will their management and harvest style differ from the current standard practice, and will it work? David shared some preliminary findings with us at Celebrate Waters.

Currently most of the forests in this area are managed in a manner referred to as ‘short rotation, even aged’. Essentially, this type of management maximizes forest products and returns to the investors/owners by harvesting trees at 40-60 years of age.

The goals of the Nisqually Indian Tribe and other stakeholders of the community forest are different; they are seeking to provide more of a balance across forest products, local jobs, salmon habitat, and carbon sequestration.

While timber is still harvested annually, a high priority is placed on providing for the needs of salmon, especially the federally threatened Nisqually Chinook and Steelhead. This change in forestry practice, moving away from ‘short rotation, even aged’ management to uneven aged management with multiple entry thinnings every 15-20 years also allows for more carbon sequestration.

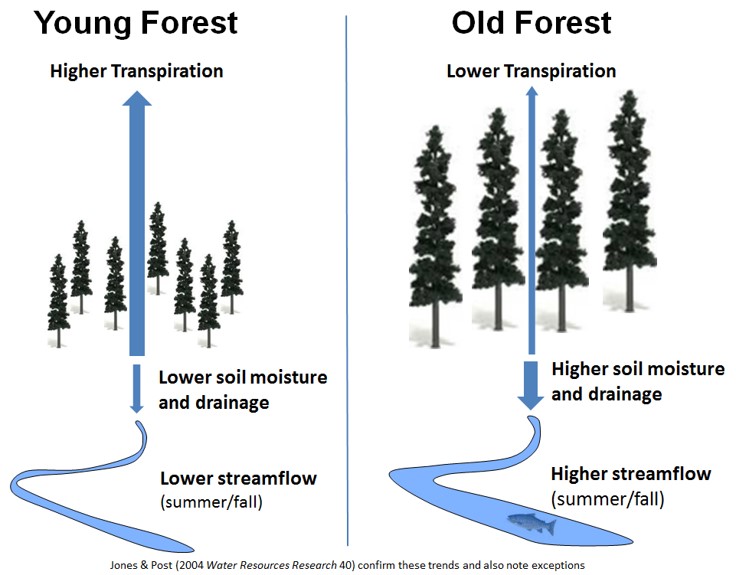

Furthermore, experimental research has demonstrated that ‘young’ forests—defined as trees less than 80 years old—grow vigorously and transpire over 3 times more water out of the soil than ‘older’ forests or those with trees closer to 100+ years in age. Other scientific data, along with anecdotal information from fishing stories and local knowledge, support the idea that older forests tend to generate substantially greater stream flow during the drier summer months.

Located just west of Mt. Rainier, 40 years ago the Mashel River was known as one of the premier steelhead and chinook salmon rivers in the PNW. More recently however, fish populations have plummeted. The decline in salmon runs has a substantial negative impact on the Nisqually Tribe, whose cultural traditions have long depended upon sustainable harvesting of salmon from Nisqually Basin streams.

In the 1980s, Nisqually fishermen spent 105 days on the river catching salmon, whereas in 2018 they only spent 8 days fishing. Like many tribal members, Willie Frank III has spent over 30 years fishing on these rivers and has never caught a steelhead.

So what’s causing the decline in summer flow? The Nisqually River Basin community suspects a significant contributing factor is forestry management. During the late 1900s, large portions of the Mashel River sub-basin were converted to young, intensively harvested forests where trees are cut at 40-60 years instead of 80-10o years.

Using a combination of modeling techniques to analyze a specific part of the Nisqually River Basin, the Mashel River Watershed, stakeholders wanted to answer the question: will an older forest with longer harvest intervals increase summer streamflow?

The answer seems to be yes.

Currently USGS gauges show an average minimum flow in August of 6 cubic feet per second. Models in which the entire Mashel sub-basin is managed at a 40 year harvest interval, that minimum is predicted to go down to 2 cubic feet per second. Conversely, if the average age of the forest is raised to 100 years, the flow is predicted to increase to 11 cubic feet per second.

Granted, models are no substitute for data collected through scientific observation and measurement, so there is no guarantee. And while increasing summer streamflows will only help, there is no “silver bullet” to saving our imperiled salmon runs. But for a new venture, the preliminary data is incredibly encouraging and worth the effort; Nisqually Community Forest managers continue to seek support and funding to purchase more timberland.

The climate crisis is here and it is going to take a broad suite of solutions to build the resilience our communities and ecosystems desperately need. We are so thankful for the leadership provided by the Nisqually Indian Tribe and other Nisqually Community Forest stakeholders; their effort is a shining example of a community standing tall to protect our local forests, fish, and ecosystems.