A new proposed federal rule from the Trump Administration revives a long-standing effort to deregulate…

Summer 2023 Drought in Washington

RCW 43.83B.011(2)”Drought condition” means that the water supply for a geographic area, or for a significant portion of a geographic area, is below seventy-five percent of normal, and the water shortage is likely to create undue hardships for water users or the environment.

WAC 173-166-030 (6)The determination of drought conditions will consider seasonal water supply forecasts and other relevant hydro-meteorological factors (e.g., precipitation, snowpack, soil moisture, streamflow, and aquifer levels)and also may consider extreme departures from normal conditions over sub-seasonal time frames.

In early July, a drought advisory was issued for all of Washington state following the warmest May on record. Coupled with only 47% of our normal rainfall between early April and late June, the advisory was issued to give water users time to prepare for an inevitable drought emergency and its related water restrictions.

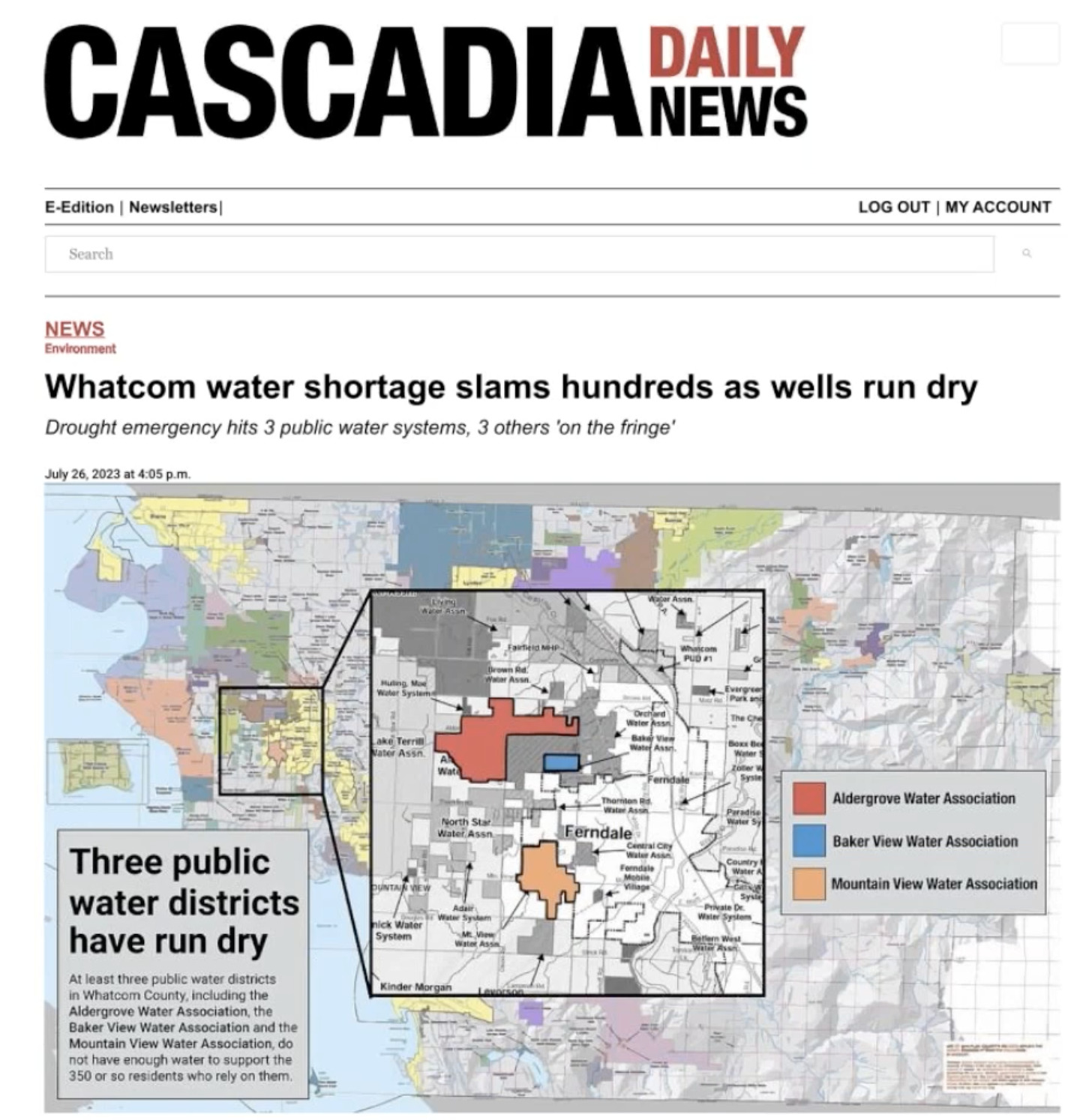

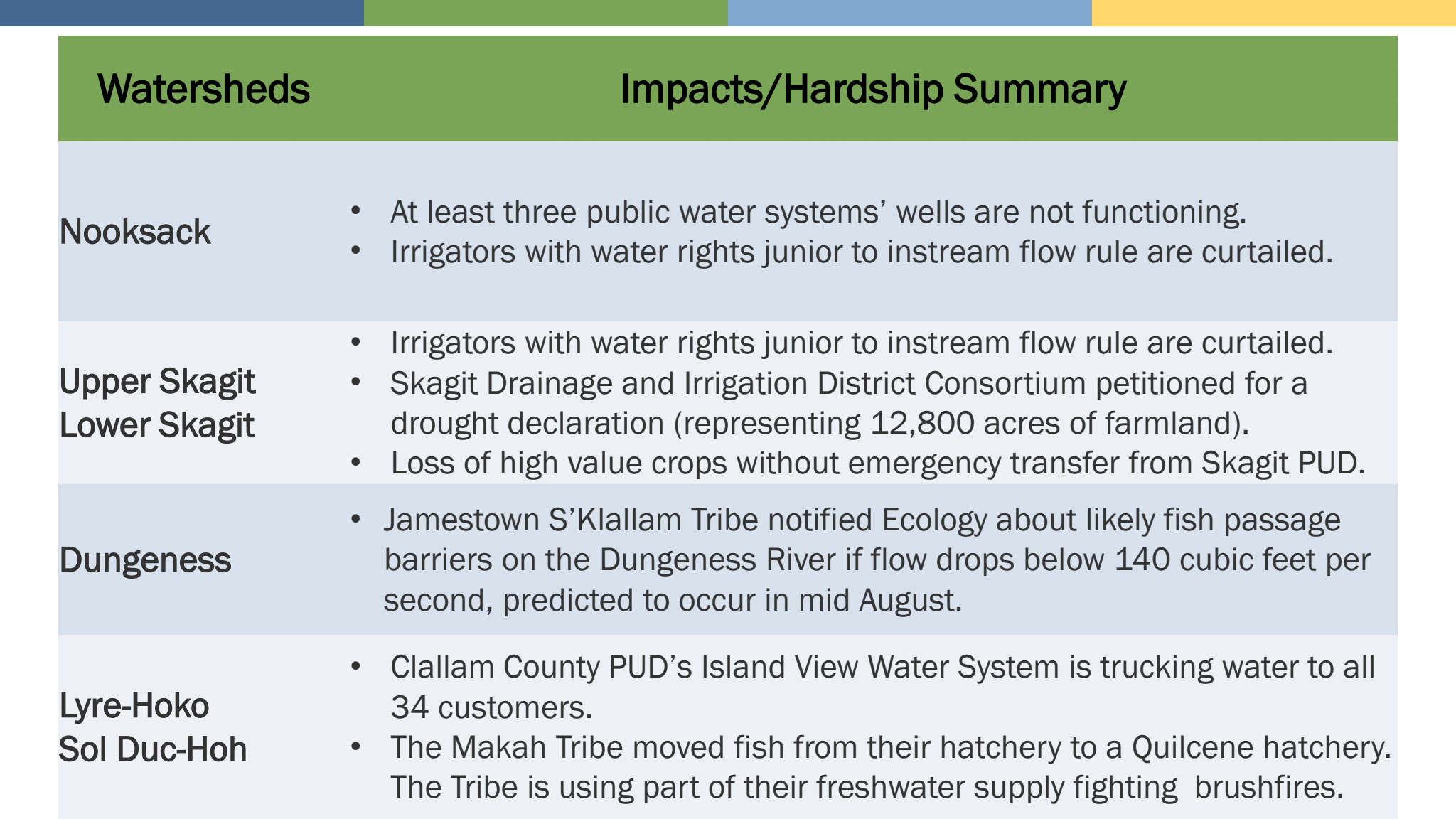

On July 27, a drought emergency was declared in parts of a dozen counties on both sides of the Cascades, including in some counties like Whatcom, Snohomish, and Skagit, where visually, it would not seem such a thing was possible. Whatcom County saw some wells going dry, with several communities trucking in water to meet household needs, and recreational water recreation on the popular Nooksack River has been curtailed, endangering businesses that depend on summer tourist dollars.

August drought conditions have continued to degrade, particularly in Western Washington. Sturgeon in the Columbia River are experiencing higher mortality rates due to high water temperatures. Skagit County is experiencing water shortages for agriculture; 30% of spring wheat crops are in poor condition, and 50% of rangeland conditions are poor. Port Angeles in Clallam County has issued voluntary water restrictions due to low streamflows on the Elwa River,

Despite recent rainfall, there is no end to the drought in sight for Western Washington. Fall forecasts predict warmer and drier than normal conditions with increased fire danger across Puget Sound. Winter conditions aren’t looking much better with a strong El Nino predicted, although it is still too soon to determine how that will actually impact precipitation levels.

As of the end of August 2023, 75% of all Washington waterways are experiencing low streamflow conditions.

How Did We Get Here?

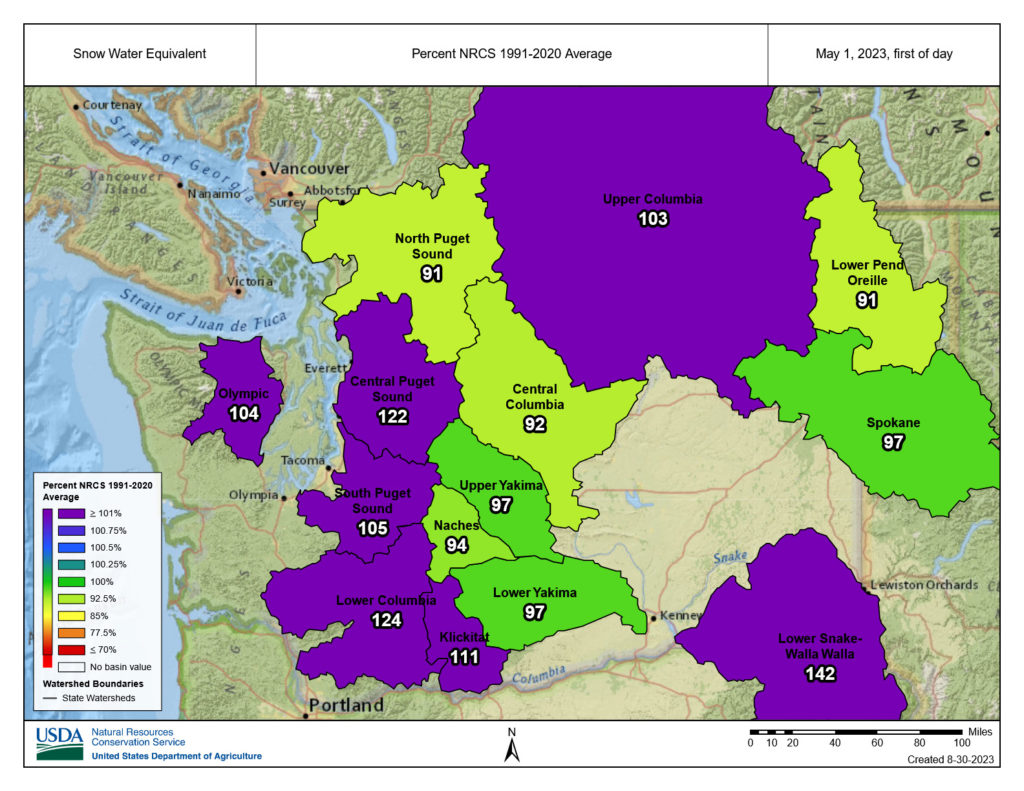

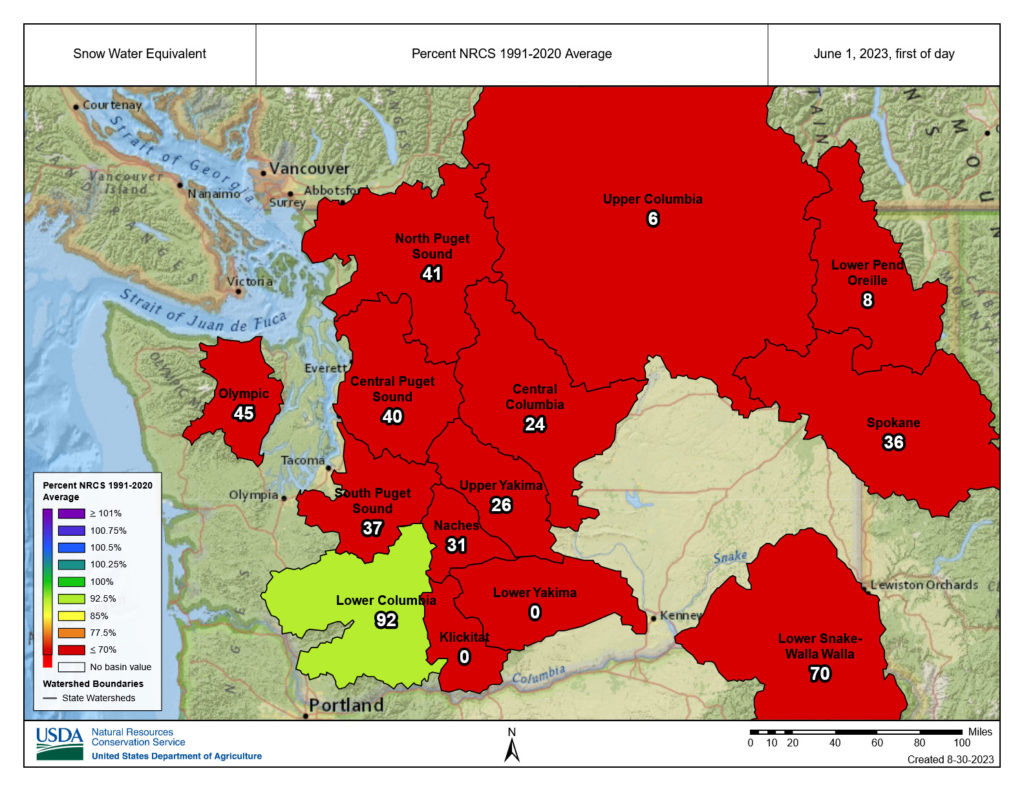

While western states shattered snowfall records during storms in late March, the snowpack in Washington peaked on April 23, about two weeks later than usual, at 111% of the normal snow-water equivalent statewide. Things looked good until mid-May when an unusual heat wave made national news, with temperatures 20 degrees above normal in Washington and Oregon, topping out at 90 degrees in the Seattle area. This accelerated snowmelt in the Cascades, and the loss of nearly half of the 34,445,826 acre-feet of water stored in snow, setting a record for rapid snowmelt.

April 1, 2023 average snow-water equivalent (1991-2020)

May 1, 2023 average snow-water equivalent (1991-2020)

June 1, 2023 average snow-water equivalent (1991-2020)

The extreme heat in May is unusual but may provide a look at our future. Projections for this fall are for dryer, warmer weather than historic averages, which would set us up for a water-challenged 2024.

Spring and fall precipitation are vital to keeping the soil moist so rain and snowmelt can join waterways and become usable to humans. If we enter winter dry, snow and ice melt water will first go to the mountain surfaces and less will end up in groundwater or streams. In short, a dry fall means a dry start to spring and that is the current projections from the Department of Ecology. It is Washington, and we have notoriously difficult weather predictions. But consider yourself warned.

Who Is Affected

A Little History

Washington is famous for its apples, wine, hops, and feed grains, all of which depend on irrigation water pulled from our river systems. The first water rules in Washington arrived with mining and, like mining claims, were established by announcing that a body of water was in use, or had been claimed by a business or individual. As the settled population boomed at the turn of the century, water conflicts increased. In 1917, the state passed its first surface water law, ensuring that the oldest holders of water rights would always have access to water. This was called the doctrine of prior appropriation, or “first in time, first in right”. The process of adjudication, or determining the validity of water rights, how much water can be used and who has priority, began nearly immediately. Since 1918, water rights in 82 river basins have completed adjudication, with the Yakima River basin being to most recent. Two other basins, the Nooksack and the Lake Roosevelt, are in the beginning stages of adjudication now.

Tribes

In 1970, the Federal government filed a lawsuit on behalf of tribes, arguing that when treaties were signed in the 1850’s they guaranteed the right to fish in usual and customary locations. In order for there to be fish, there must be habitable, consistent water flow in the rivers and tributaries in which salmon return to spawn and for the young to grow. Without some measure of control over the off-reservation impacts to water availability, depth, flow, and overall health, tribes argue their treaty rights to fish are being adversely impacted.

Tribes in Washington have the most senior water rights because they have been in Washington State for much longer than settlers. Tribes have water rights both within and outside of their reservations. The off-reservation water rights are designated to leave enough water remaining in rivers and streams for healthy salmon populations. This water right is tied to their treaty-given right to fish, and is especially important when salmon return to spawn in the summer when water shortages are common. (ReSources)

Most tribes in Washington do not have their water rights quantified – meaning, a determination has not been made about how much water is necessary, where, and for what – because the legal system is slow to comprehend and act on the full extent of the treaty-given rights clarified in Boldt. Without quantifying off-reservation (upstream/groundwater) water rights in particular, there is no way to enforce or protect Tribal water rights, or the treaty rights to fish as determined by the Boldt decisionCurrently, the only federally recognized tribe that has gone all the way through the adjudication process is the Yakima. The adjudication process has begun for the Lummi Nation and Nooksack river in the Nooksack watershed, and will soon begin for the Colville Tribe.

As Washington faces drought again and again and is losing the battle to retain healthy salmon populations, the argument regarding whose rights to water matter becomes literally even more heated.

Fish

Washington has almost 74,000 miles of rivers and streams, more than 4,000 lakes and 3,000 square miles of marine estuaries. Many of these water bodies provide critical habitats for species that depend on cool, clean, dependable flows of water – especially our native salmon populations. As drought conditions reduce water flow, the shallower water heats up faster and creates water too warm for them to thrive. And summer streamflow is reduced to zero or near zero in many streams. Keeping abundant water in streams for salmon is a priority for Tribal communities and for Washingtonians concerned about the health of all our non-human species.

Communities

According to the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA), 75 percent of Washington’s total water supply is from surface water and 25 percent is from groundwater. However, over 60 percent of drinking water in Washington State is supplied by groundwater. More than 6.2 million Washington State residents (85% of the population) get their drinking water through these public water systems, with the remainder of the water coming from private wells. It is estimated that over 30% of all usage of water is for landscaping, amounting to 9 billion gallons per day across the nation. As climate change impacts both ground and surface water, all communities will likely face water restrictions, decreased water abundance, or suffer the loss of existing systems without aggressive commitment to water conservation.

Farms

In Washington, 80% of Washington water withdrawals are for agriculture, with most large farms located in the sunny and dry eastern part of the state. Climate change is increasing the frequency of drought conditions as less water moisture is occurring as snow or rain, and increased extreme weather events make it difficult to predict and manage water or dry conditions. Most of the large farms have “senior” water rights, meaning they have held – and used the water right the longest. These users are the last to see restrictions on their usage. Smaller or newer farms have “junior” water rights, meaning that in a time of drought, these small farms are the first to be required to reduce their water usage. But farms are not the only major users of water.

What Needs To Be Done

In recent years, we have created pathways to fund emergency water supplies to help farmers, fish and people during drought and encouraged the leasing of water, but more needs to be done to make better use of our dwindling water supply.

What You Can Do

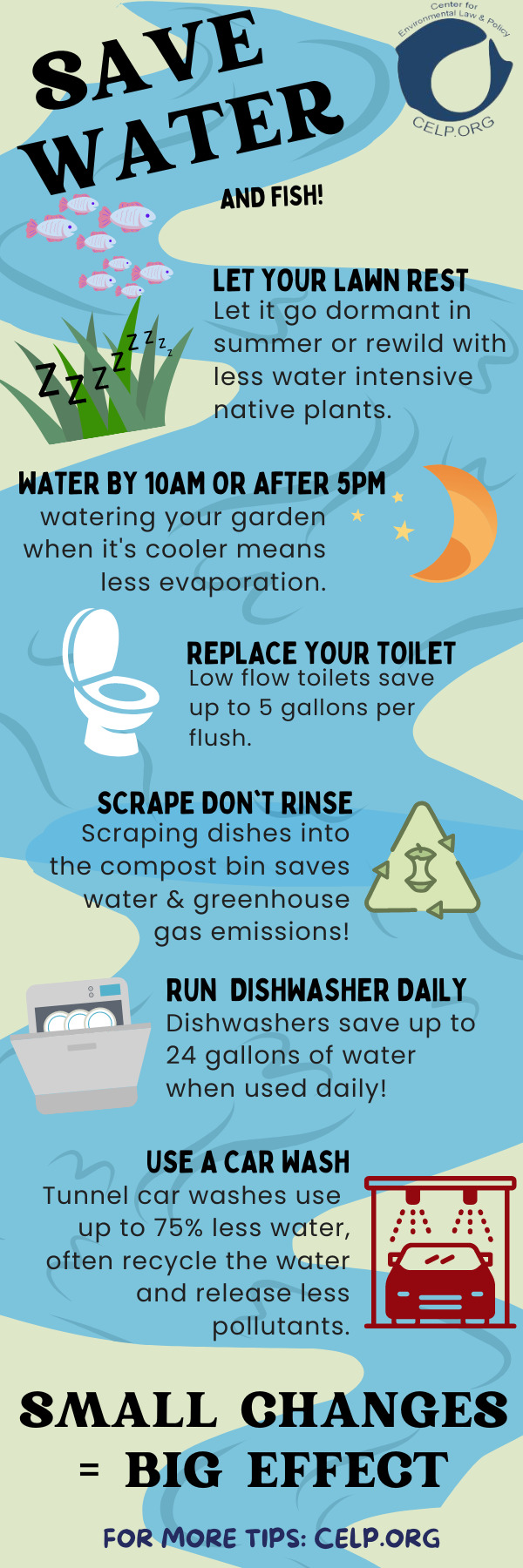

As individuals, communities and nations face a water challenged future, we are often left with a sense that nothing we can do will really matter in the long run. We can assure you, that is not correct. Simple, small changes add up to significant decreases water reduction and waste water production, saving our most precious resource for the lives in our communities, forests and waterways.

Using water-saving techniques can save you money and diverts less water from our rivers, bays, and estuaries, which helps keep the environment healthy. It can also reduce water and wastewater treatment costs and the amount of energy used to treat, pump, and heat water. This lowers energy demand, which helps prevent air pollution.

It’s not just the dry western areas of the country that need to be concerned with water efficiency. As our population continues to grow, demands on precious water resources increase. There are many opportunities to use household water more efficiently without reducing services. Homes with high-efficiency plumbing fixtures and appliances save about 30 percent of indoor water use and yield substantial savings on water, sewer, and energy bills. Start saving today.

Top Five Ways to Save

- Stop leaks. Check all water-using appliances, equipment, and other devices for leaks. Running toilets, steady faucet drips, home water treatment units, and outdoor sprinkler systems are common sources of leaks.

- Replace old toilets. The major water use inside the home is toilet flushing. If your home was built before 1992 and you haven’t replaced your toilets recently, you could benefit from installing a WaterSense labeled model that uses 1.28 gallons or less per flush. A family of four can save 16,000 gallons of water per year by making this change.

- Replace old clothes washers. Washers are the second largest water user in your home. If your clothes washer is old, you should consider replacing it with an ENERGY STAR certified clothes washer. Most ENERGY STAR clothes washers use four times less energy than those manufactured before 1999. To save more water, look for a clothes washer with a low water factor. The lower the water factor, the less water the machine uses. Water factor is listed on the certified product list.

- Install WaterSense labeled faucet aerators and showerheads. WaterSense labeled products use at least 20 percent less water than standard models, while providing equal or superior performance. By installing WaterSense labeled faucet aerators and showerheads, the average family can save nearly 3,500 gallons of water and nearly 410 kilowatt-hours of electricity per year.

- Plant the right plants. Whether you’re installing a new landscape or changing the existing one, select plants that are appropriate for your climate. Consider landscaping techniques designed to create a visually attractive landscape by using low-water and drought-resistant grass, plants, shrubs, and trees. If maintained properly, climate-appropriate landscaping can use less than one-half the water of a traditional landscape.

- Provide only the water plants need. Automatic landscape irrigation systems are a home’s biggest water user. To make sure you’re not overwatering, adjust your irrigation controller at least once a month to account for changes in the weather. Better yet, install a WaterSense labeled irrigation controller, which uses local weather and landscape conditions to water only when plants need it. Install a rain shutoff device, soil moisture sensor, or humidity sensor to further control irrigation.

For more information on how you can save water, visit EPA’s Using Water Efficiently: Ideas for Residences (PDF, 995 KB).