Wildfires

The risk and extent of wildfires in the western United States is growing because of climate change. Wildfires pose a significant risk to healthy waterways in Washington.

Wildfires Are a Water Issue

The rising temperatures caused by climate change and increased wildfire risk go hand in hand. As snow melts earlier in the season, the ground dries faster, and droughts are worse and more prolonged. Dry, dead debris from weather events or insect infestations (also worse because of climate change) becomes tinder for fires that are hotter and grow faster fed by warm winds and dry soil.

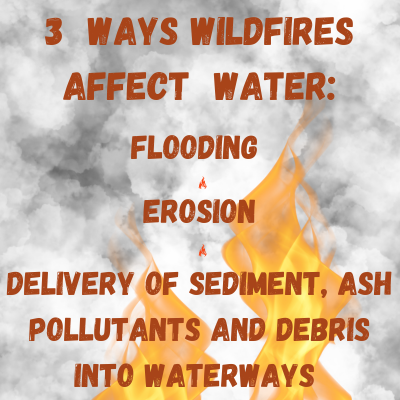

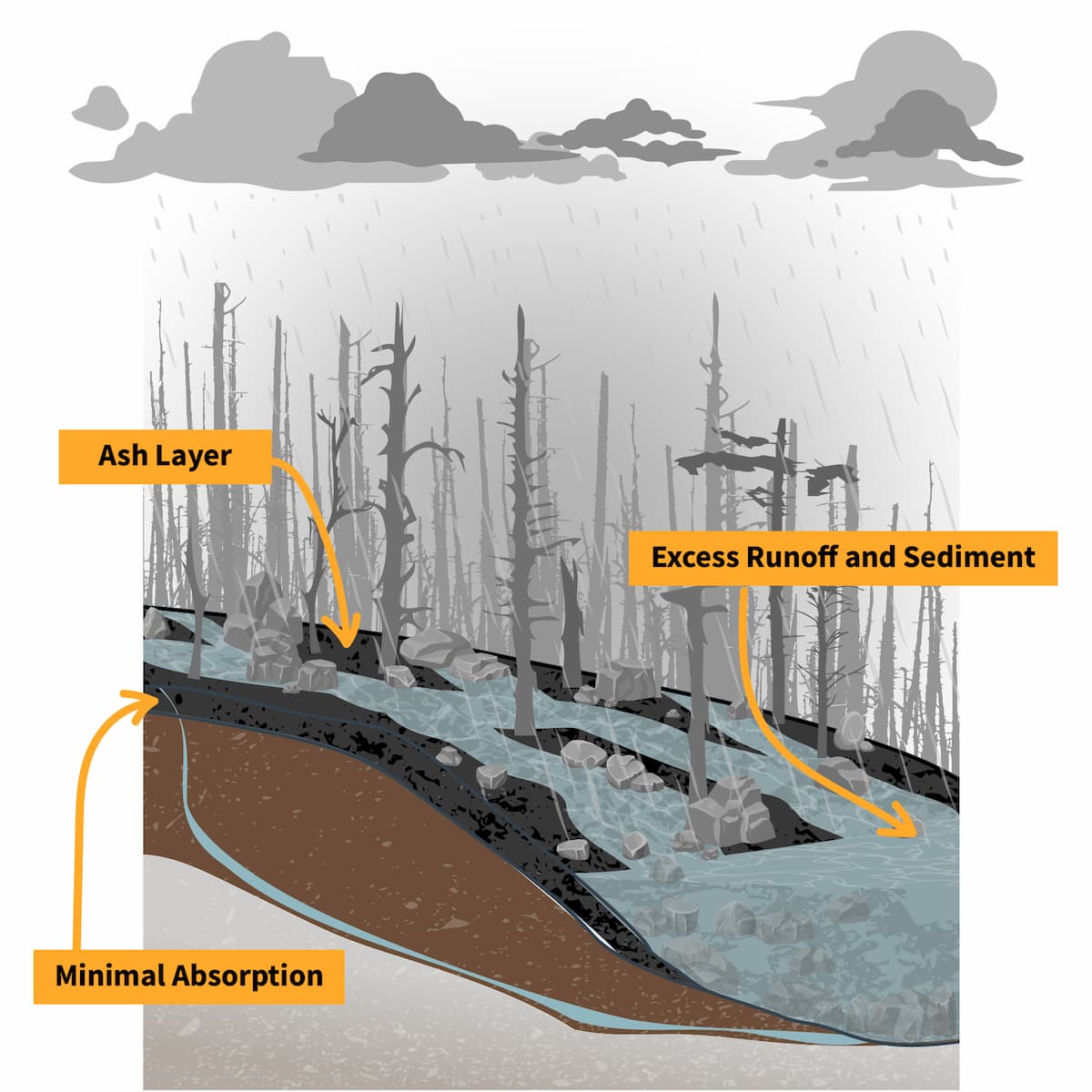

After wildfire, loss of canopy vegetation and changes to soil properties can result in more water flowing over the land surface during storms, leading to flooding, erosion, and delivery of sediment, ash, pollutants, and debris to surface water.

If a burn happens along a waterway, the loss of vegetation that previously provided shade to the waterway results in water temperatures rising. This temperature change can be enough to make the waterway lethal to salmon and other species and facilitate the growth of unhealthy algae blooms.

How Wildfires Change Watersheds

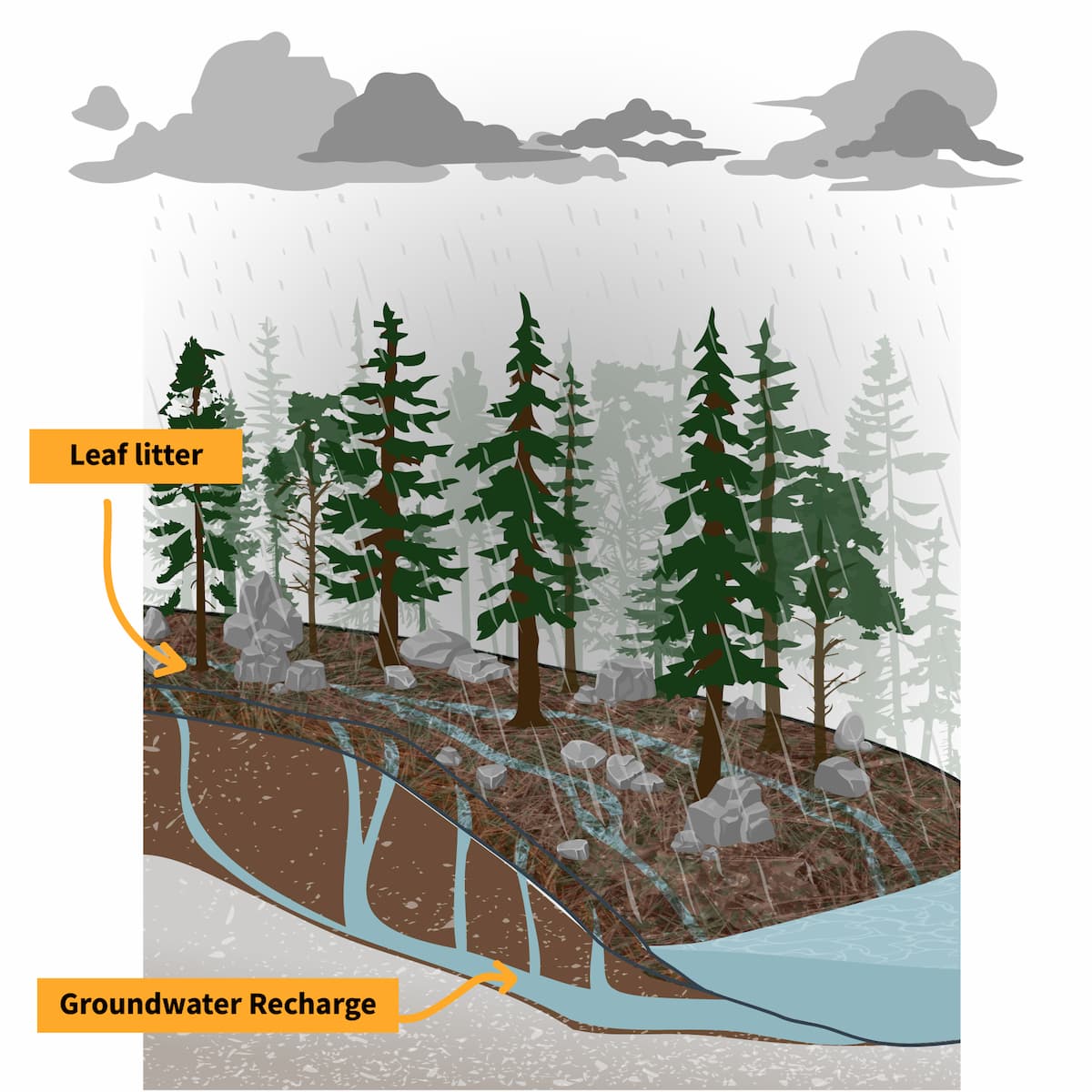

Forests, to a hydrologist’s eye, act as both a sponge and a filter. When rain falls on a forest, trees and other plants use the water to grow and reproduce. Leaves and branches, as well as layers of leaf litter on the forest floor, intercept water before it reaches the ground and protect the soil from erosion. When water reaches soil, it is soaked up then slowly released to streams, which helps recharge groundwater aquifers and reduce the risks of rapid flooding. As the water moves through soil and rock, the soil and rock act as a filter, removing contaminants. Water flowing from forested watersheds often needs only minimal treatment before drinking. (text & images below from USGS)

Wildfires & Water Quality

Just as wildfires impact air quality, they can also affect the quantity and quality of water available. Water supplies can be adversely affected during the active burning of a wildfire and for years afterwards. During active burning, ash and contaminants associated with ash settle on streams, lakes and water reservoirs. Vegetation that holds soil in place and retains water is burned away. In the aftermath of a large wildfire, rainstorms flush vast quantities of ash, sediment, nutrients and contaminants into streams, rivers, and downstream reservoirs. The absence of vegetation in the watershed can create conditions conducive to erosion and even flooding, and naturally occurring and anthropogenic substances can impact drinking water quality, discolor recreational waters, and may potentially contribute to harmful algal blooms. (EPA)