Tribal Treaty Rights

In the 1850s, many tribes in Washington signed treaties ceding their lands in exchange for fishing rights. Today, with salmon on the brink of extinction, those treaties are fated to become meaningless… unless we act.

Understanding the History

Since Time Immemorial

Indigenous Peoples have sustainably managed the lands and waters of Washington long before westward expansion, colonization, and the founding of the first natural resource agencies. Their traditional ecological knowledge of the lands and waters have been cultivated, adapted, and shared over many generations. This expansive reservoir of knowledge and deep connection to flora and fauna fosters a harmony that keep Native communities and our ecosystems strong. In fact, the UN’s May 2019 Global Assessment Report on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services found that environmental impacts were less severe or entirely avoided in areas held or managed by Indigenous peoples and local communities. Washington’s tribes continue to act as stewards for our natural resources, sharing the wisdom of their traditional knowledge to advocate and build a more sustainable relationship amongst all Washingtonians with our lands and waters.

Treaties of the 1850s

They made us many promises, more than I can remember, but they never kept but one; they promised to take our land, and they took it.

— Chief Red Cloud, Oglala Lakota

As white settlers moved West, the tribes of what is now the state of Washington knew they had few options; they could fight an unwinnable war, or sign treaties ceding most of their land to live on reservations. They chose not to fight.

Knowing that the right to fish was of upmost importance to tribes, territorial Governor Isaac Stevens included the same provision in all treaties: “The right of taking fish at usual and accustomed grounds and stations is further secured to said Indians in common with all citizens of the Territory, and of erecting temporary houses for the purpose of curing, together with the privilege of hunting and gathering roots and berries on open and unclaimed lands. Provided, however, that they shall not take shell-fish from any beds staked or cultivated by citizens.” For a short while there was little conflict—fish were plentiful and the ecosystems still healthy—but at the 19th century came to a close, colonial practices started to take a toll. Technological advances (canning + fish wheels) allowed for fish to be stored and shipped worldwide and commercial fishermen to fish far more efficiently to meet increased demand. At the same time, the detrimental impacts of clear cut logging and non-regenerative agriculture led to a decline in watershed health and water quality. Salmon yields in various rivers of the Pacific Northwest peaked between 1882 and 1915. Since then, the salmon and their fisheries have been in continuous decline.

As tribes saw fewer fish returning to their rivers they began to harvest off-reservation—a right established by the treaties—but when put into practice, tribal fishermen were arrested and jailed, and their gear and catch confiscated.

The Fish Wars

Despite U.S. Supreme Court rulings affirming tribal treaty rights, the state of Washington continued to enforce discriminatory laws against tribes. Tensions continued to grow until reaching a fever pitch in the 1960s. Modeling civil disobedience tactics utilized by the Civil Rights Movement, tribes fought to protect their sovereignty and treaty rights by hosting “Fish-Ins”. Clashes between tribal and non-tribal fishers grew violent; shots were fired, protesters beaten and gassed, boats overturned and rammed, a bridge in Puyallup set on fire.

Once somebody stood up to the state of Washington, the gaming department, the state fisheries—you knew you were going to get beat up. You knew you were going to go to jail. You knew this was going to happen.

— Don McCloud (Puyallup), NMAI Interview, July 2016

The Boldt Decision

In 1970, the federal government filed United States v. Washington on behalf of the tribes, arguing the state was denying tribes rights guaranteed in treaties signed in the 1850s. The trial began in August 1973 and the decision issued in February 1974. A complex, 203-page decision, it sent shock-waves through the country by interpreting the treaty language “in common with” to mean that tribes were entitled to up to 50 percent of the harvestable catch. At the time, Indigenous Peoples accounted for roughly 1% of the population of Washington and non-tribal fishers were taking up to 95% of the catch. The Boldt Decision also established tribes as co-managers, established conservation standards, restricted the ability of the state to regulate treaty fishing, and affirmed that for the treaty to have meaning there must be fish available.

Where We Stand Today

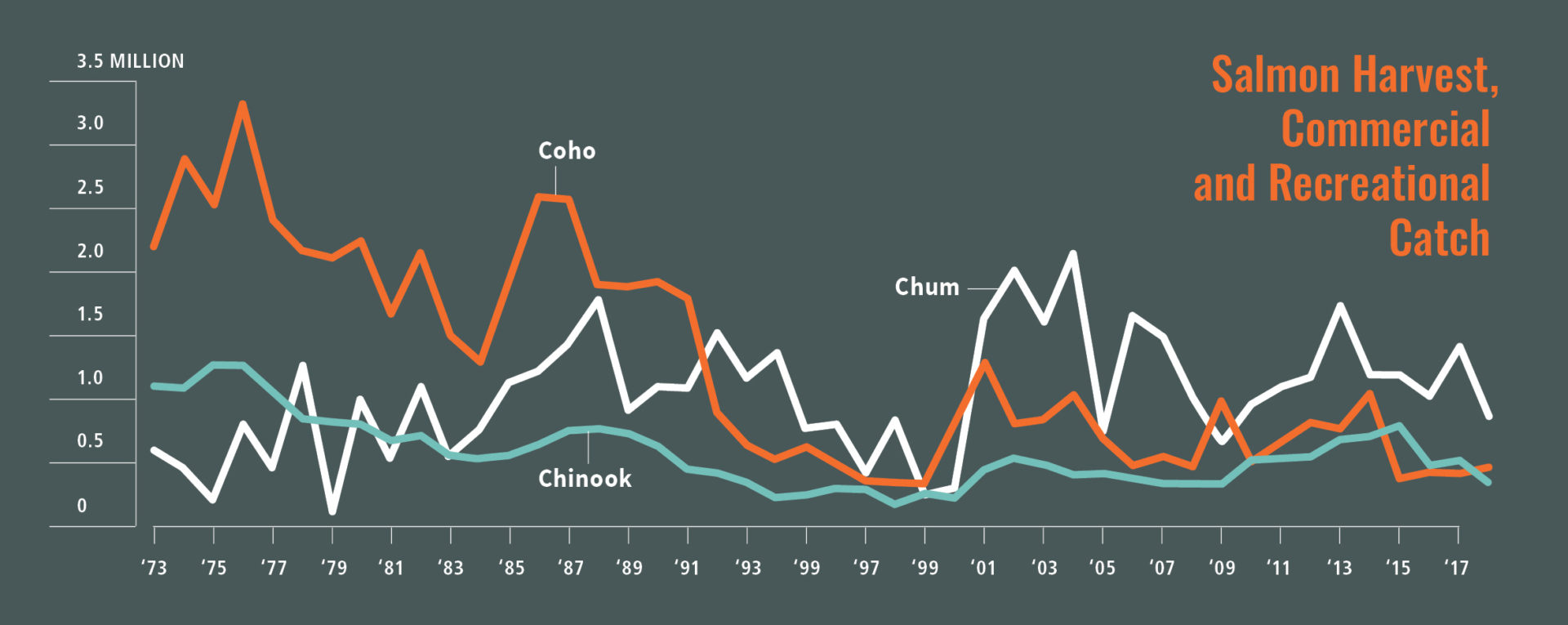

Over the past four decades, Washington has dedicated a significant—albeit lacking—amount of money ($1 billion between 2010-2019 alone) to salmon recovery. Government, tribes, and NGOs have also enacted and enforced massive cuts in harvest, strategically utilized hatcheries, and implemented critical habitat restoration projects across the state. But despite this massive investment in time, money, and energy, we are losing the battle for salmon recovery. As their habitat is destroyed quicker than it can be recovered, salmon continue to decline. As the salmon disappear, so do tribal cultures and treaty rights.

Figures provided by the 2020 State of Salmon in Watersheds Report

Working For Restorative Justice

Our country was conceived on a promise of equality and opportunity for all—a promise we have never fully lived up to. As we aspire to remedy the atrocities of the past, we seek decolonization by dismantling the structures that created, and perpetuate, a system of exploitation and unbalanced power dynamics. CELP is committed to respect and support Tribal sovereignty, co-management responsibilities, authorities, and rights, to share a healthy, productive environment for all. It is with gratitude and humility that we acknowledge and honor their wisdom and invaluable traditional knowledge by ensuring we center our tribal partners’ needs, goals, and strategies in our work.

Legislature Funds Nooksak River Basin Adjudication

In support of Lummi Nation and the Nooksack Indian Tribe, CELP wrote a letter to the Washington Department of Ecology urging them to select the Nooksack River for the next basin to be adjudicated. We also lobbied the state legislature during the in support of the Governor’s proposed operating budget (SB 5092), which included the funding needed critical to starting the adjudication process.

In April 2021, the State Legislature appropriated funds for Ecology to begin the adjudication process. As stated in response by Chairman Ross Cline Sr. of the Nooksack Tribe, “We thank the Governor and legislators; this is a good step and is the only legal path we have in Washington to make sure there’s enough water in the Nooksack River for salmon, farming, and people. Climate change is upon us and the sooner we get started, the sooner we can find solutions for water.”

Legal Support Leads to 'Swinomish Decision' Preserving Skagit River Instream Flow

Along with partner Earthjustice, CELP filed a friend of the court brief with the Washington State Court of Appeals in support of the Swinomish Indian Tribal Community and its ongoing effort to protect the Skagit River and salmon. In the brief, Earthjustice and CELP argued that Ecology cannot allow more water to be withdrawn from the troubled Skagit River and its tributaries for new junior water uses because such new uses would further impair stream-flows.

Ultimately, the State Supreme Court ruled in favor of the Swinomish Tribe in 2013.

“This decision is a huge victory for Swinomish, for salmon and for the water that salmon need to survive,” said Swinomish Chairman Brian Cladoosby. “Ecology had a choice to do the right thing or the wrong thing in 2006, and unfortunately, it chose to do the wrong thing. The court’s decision vindicates the tribe’s position and confirms that Ecology cannot make an ‘end run’ around laws that protect instream flows for fish.”

Organized International Coalition to Modernize Columbia River Treaty

In April 2013 CELP and Save Our Wild Salmon, with help from the Northwest Fund for the Environment, brought together a coalition of 12 environmental organizations to form the Columbia River Treaty NGO Treaty Caucus. In alliance with the 15 Columbia River Tribes, the Caucus is advocating for an updated Treaty that does the following:

- Makes restoring the Columbia River’s ecosystem a primary purpose of the Treaty, equal with power production and flood control;

- Takes real steps to redress the old Treaty’s injustices to the Columbia Basin’s native people, salmon, and the ecosystem; and

- Provides a framework to help people in the Northwest and British Columbia respond to the unprecedented impacts climate change is detonating in our waters and lives

Entered Litigation to Defend Dungeness River Rule

In support of the Jamestown S’Klallam Tribe, CELP intervened to deny a challenge to the Dungeness Instream Flow Rule from a group of property owners and developers. “The Dungeness water rule is truly a water resource management rule,” said Scott Chitwood, the tribe’s natural resources director. “It recognizes the connectivity between surface water and groundwater.

CELP Staff Attorney Dan Von Seggern argued the case along with Ecology’s attorneys and Thurston County Superior Court Judge Gary Tabor ultimately passed a decision upholding the Rule in October 2016.

Fighting to Free the Similkameen River

A major tributary to the Okanogan River, the Similkameen flows through 122 miles of potential salmon habitat in British Columbia and Washington. A fish-blocking dam was constructed on the River in 1922 and has not generated power since 1958. The Okanogan County Public Utility District (PUD), which owns the dam, is attempting to restart power generation at the dam. The power the dam would produce is not needed and would be much more expensive than the PUD’s current sources of electricity.

On September 13, 2018, along with the Sierra Club and Columbiana, CELP filed a Notice of Intent to Sue the Okanogan County PUD as well as the National Marine Fisheries Service (NMFS) and the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission (FERC) over the dam’s effect on ESA-listed Upper Columbia steelhead and Chinook salmon. The Notice is the first step towards filing a lawsuit under the Endangered Species Act. We contend that the dam unlawfully harms ESA-listed fish species, that the process of evaluating the dam’s impact on fish was inadequate, and that FERC unlawfully failed to consult with NMFS regarding the listed fish, as the Endangered Species Act requires.