Drought In Washington

Regardless of Washington being known as “The Evergreen State”, the future looks less green if we are not careful.

Should We Be Worried About Drought?

The entirety of the West is currently in the midst of a 20+ year megadrought that is unlikely to end anytime soon. A 2022 study analyzing tree rings has determined the drought that started in 2000 is now the driest two decades in over 1,200 years. It’s yet another example of the data clearly indicating how unusual current conditions are. The study also confirms the role of temperature, more than precipitation, in driving exceptional droughts. Precipitation amounts can vary over time and by region, but as humans continue to pump greenhouse gasses into the atmosphere, temperatures most everywhere are consistently rising. Drier and warmer, the air is essentially more capable of pulling water out of our ecosystems—from natural reservoirs of moisture such as soil and plants—it makes for drought conditions to be much more extreme than if climate change wasn’t a factor.

How did we get here?

Since the Industrial Revolution, human activities have released large amounts of carbon dioxide and other greenhouse gases into the atmosphere, which has changed the earth’s climate. Natural processes, such as changes in the sun’s energy and volcanic eruptions, also affect the earth’s climate. However, they do not explain the warming that we have observed over the last century

Concentrations of theses gases have all increased due to human activities. Carbon dioxide, methane, and nitrous oxide concentrations are now more abundant in the earth’s atmosphere than any time in the last 800,000 years.5

They act like a blanket, making the earth warmer than it would otherwise be. This process, commonly known as the “greenhouse effect,” is natural and necessary to support life. However, the recent buildup of greenhouse gases in the atmosphere from human activities has changed the earth’s climate and resulted in dangerous effects to human health and welfare and to ecosystems. Greenhouse gas emissions have increased the greenhouse effect and caused the earth’s surface temperature to rise.

Warmer temperatures enhance evaporation, which reduces surface water and dries out soils and vegetation. This makes periods with low precipitation drier than they would be in cooler conditions.

Historical Drought Conditions in Washington

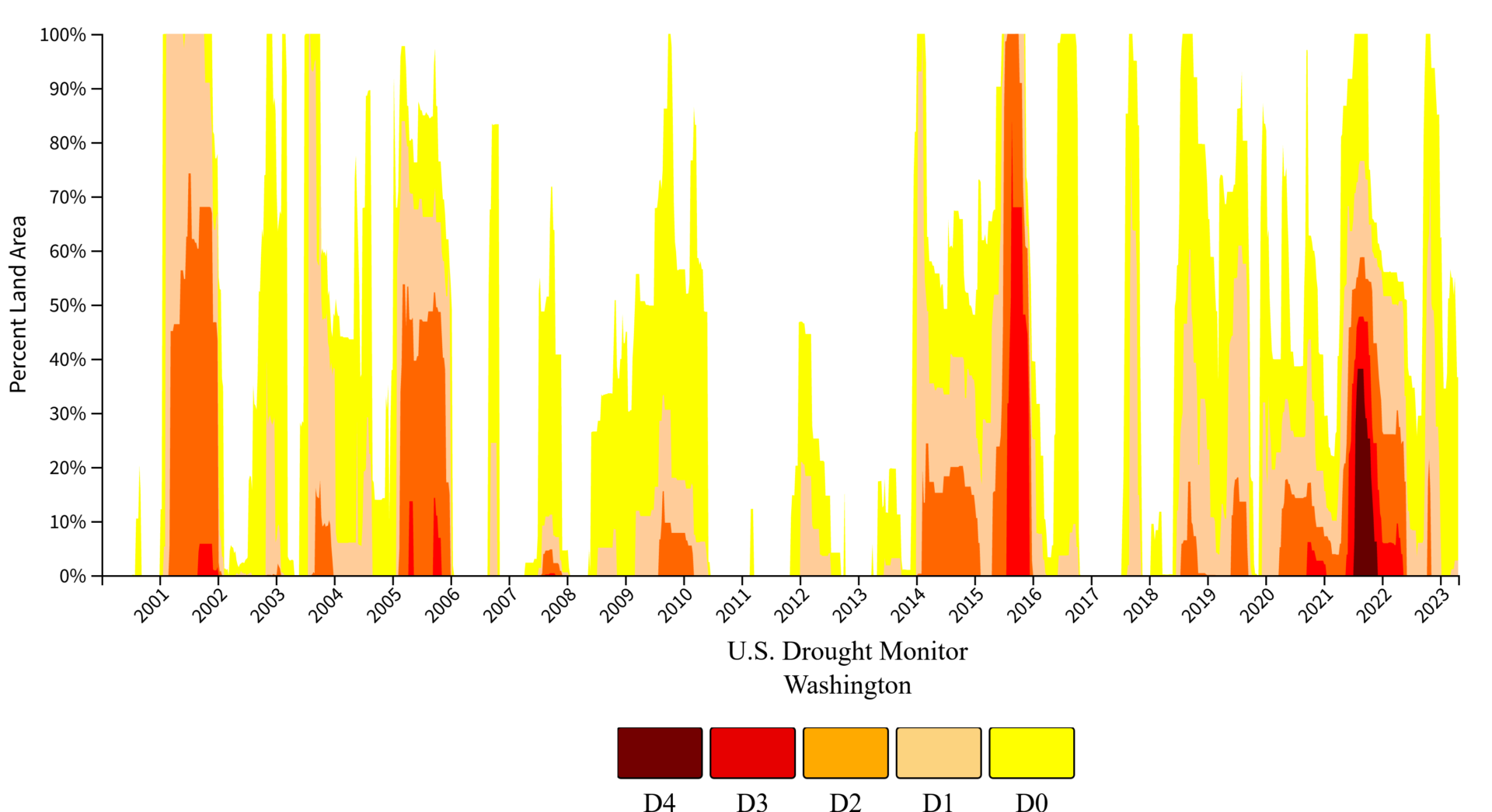

On the map to the right, you can look at past drought conditions for Washington according to 3 historical drought indices. The U.S. Drought Monitor is a weekly map that shows the location and intensity of drought across the country since 2000. The Standardized Precipitation Index (SPI) is a monthly depiction of drought based on precipitation (with data going back to 1895). And the paleoclimate data uses tree-ring reconstructions to estimate drought conditions before we had widespread instrumental records, going back to the year 0 for some parts of the U.S. View more historical conditions. (Source: Washington Dept. of Ecology)

The U.S. Drought Monitor (2000–present) depicts the location and intensity of drought across the country. Every Thursday, authors from NOAA, USDA, and the National Drought Mitigation Center produce a new map based on their assessments of the best available data and input from local observers. The map uses five categories: Abnormally Dry (D0), showing areas that may be going into or are coming out of drought, and four levels of drought (D1–D4). Learn more.

Where are we going?

By 2050, the severity of widespread summer drought is in Washington state is projected to quadruple. Among all US states, Washington is expected to suffer the single greatest increase—both in percentage terms and in terms of absolute change—far above average for both. Just as drought threat varies from state to state, the impacts of climate change on drought conditions within Washington will vary from county to county. The Yakima Basin in particular, is incredibly vulnerable to drought.

The arid lowlands of the Yakima River Basin, in which include the major population and business centers and agricultural production and processing areas, receive approximately 10 inches of rain per year. The major reservoirs have a relatively low capacity to capture runoff volumes. Snowpack is a critical water source accounting for more than half of the basin’s water supply. A “snowpack drought” happens during water years when warmer than normal temperatures cause more moisture to fall as rain rather than snow, and the snow that does fall melts earlier in the year. The result is more water flowing down rivers and streams earlier in the year. This, combined with it’s relatively small reservoir capacity, means less water for food production, municipalities, and fish later in the year. (source: Yakima-Integrated-Plan-Executive-Summary-and-Full-Report)

The Long-Term MIDI approximates drought impacts from changes in precipitation and moisture over a long-term timeframe (up to 5 years), such as impacts to irrigated agriculture, groundwater, and reservoir levels. Long-term drought conditions can also increase wildfire intensity and severity. (Source: Washington Dept. of Ecology)

A look at how Climate Change may impact one of Washington’s River Basins – The Yakima