A new proposed federal rule from the Trump Administration revives a long-standing effort to deregulate…

A Warning from the Yakima: Washington’s Water Future in a Warming Climate

Cle Elum Reservoir, Upper Yakima Basin, October 2025 – Photo: Chris Wilke/CELP

By Stephanie Hartsig, Creative Climate Lab and Chris Wilke, Center for Environmental Law & Policy. Data Visuals By Mark Rubin, Creative Climate Lab

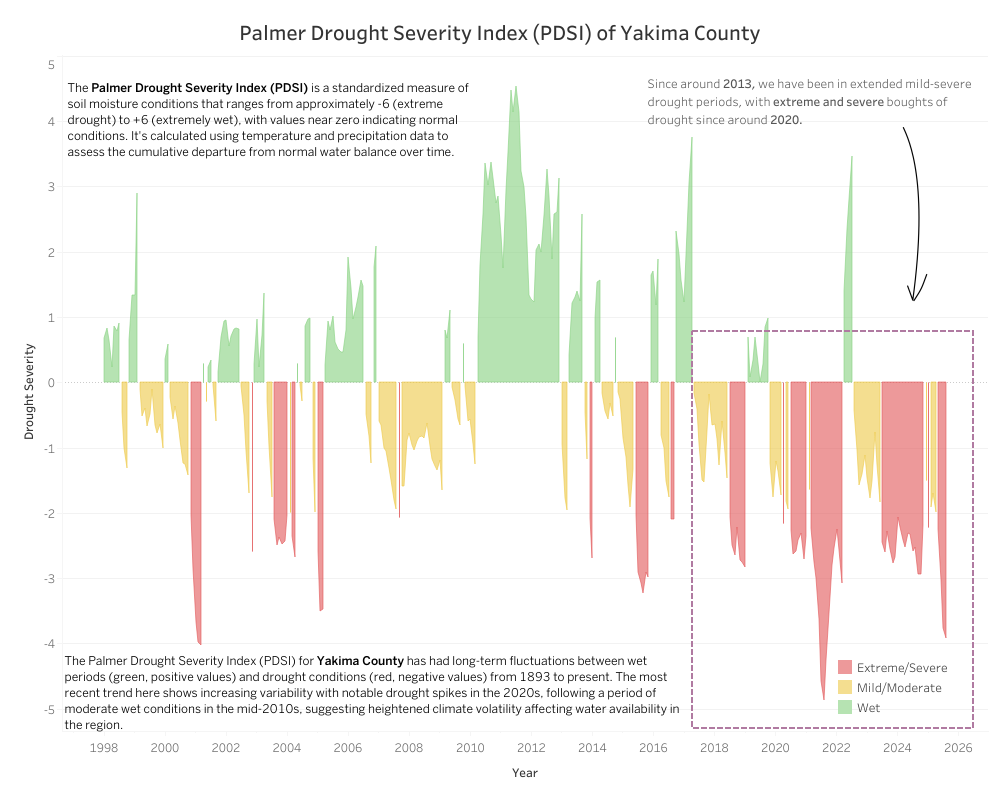

In the heart of central Washington, the increasing warming of our planet is redefining what water scarcity looks like. In response to an ongoing three-year drought, the Washington Department of Ecology ordered a halt to almost all surface-water diversions from the Yakima River between October 6 through October 31, 2025, citing extremely low reservoir storage and poor streamflows.¹ For the first time, only the most senior water rights were honored, including rights that originate from the 1855 Treaty with the Yakama Nation. The basin’s five reservoirs were at historic lows — as low as 8% full — about a quarter of their typical volume for October.2

Two primary conditions set the stage for this past October’s unusually low water stores. In dry years, the basin’s water rights exceed reliable supplies leading to prorationing and curtailment when runoff is low.3 At the same time, a warming climate is shifting hydrology toward reduced snowpack, earlier snowmelt runoff, and lower summer flows that intensify late-season shortages.4 In the Yakima Basin, snow supplies about 75% of annual runoff, so declines and timing shifts in snowpack have outsized effects on water available for people and ecosystems.5

Cle Elum River, Upper Yakima Basin – Photo: Chris Wilke/CELP

The current drought —combined with more than a century of artificial water management in the basin —has particularly strong impacts on salmon, trout, and other fish that depend on clean, cold water to survive. Upstream of the major river diversions, flows and fish habitat in the middle basin are relatively healthy, and a thriving year-round recreational trout fishery draws anglers to the river. But downstream, the salmon that migrate through the lower river face a far different scenario: with dwindling flows, flow timing controlled by reservoir operations rather than natural snowmelt cycles, and poor water quality.

The Yakima River includes populations of steelhead trout and bull trout that are listed under the Federal Endangered Species Act (ESA).6 7 Beyond these ESA-listed species, the Yakima Basin once supported thriving coho and sockeye runs that ultimately vanished as fish-passage barriers, development, water management, and overharvest took their toll. The Yakama nation is currently working to reestablish and restore these species from nearby stocks.8 Though not officially endangered in this part of the state, highly prized Chinook salmon in the basin are extremely sensitive to many environmental factors leading to their populations being closely watched and restoration efforts focused on their recovery.9

Spawning Sockeye Salmon – Photo: Tom Ring

Understanding how water moves through the heavily engineered systems of the Yakima Basin helps explain why shifts in snowpack and timing have such large effects on supply and demand. The basin’s five reservoirs store spring snowmelt to help meet irrigation demand later in the season, but with capacity for only about 30% of the annual runoff, the system is highly sensitive to the timing of spring and summer flows.3 During irrigation season, major diversions between Roza and Parker, which sit just upstream and downstream of the city of Yakima, often leave the lower river with very little water. In dry years, flows in this stretch can shrink to only a few hundred cubic feet per second.10 11 Near Parker, a U.S. Geological Survey found that irrigation diversions can reduce summer streamflow by as much as 80%.12 Farther downstream, most of the water that remains in the river isn’t natural flow at all — roughly 80% comes from agricultural return flow (water that has already been used to irrigate crops and then drains back into the river).10 As a result, the water in the lower Yakima River closely resembles that of agricultural drains (carrying similar levels of nutrients, sediments, and other substances associated with farm runoff).10

Low summer flows exacerbate water-quality stress. The Washington State Department of Ecology’s Yakima assessments show that warm temperatures, lower dissolved oxygen, and nutrient enrichment degrade habitat for salmon and other aquatic life during the low-flow season.13 These conditions mirror projections from the Washington Department of Ecology and a 2014 Climatic Change special issue, which together depict the Yakima Basin shifting from a mixed rain-and-snow “transition” basin toward a more rain-dominated system.13 14 Modeling studies forecast a move from spring snowmelt-driven streamflows to a pattern dominated by higher winter flows and reduced summer runoff, with late-season streamflows declining and water temperatures rising by about 1–2 °C.14 Researchers warn that these shifts will narrow the cold-water refuges fish depend on, make it harder for salmonids to grow during the summer, and increase seasonal obstacles to migration and rearing unless restoration work, streamside vegetative buffers, and flow protections are strengthened.14

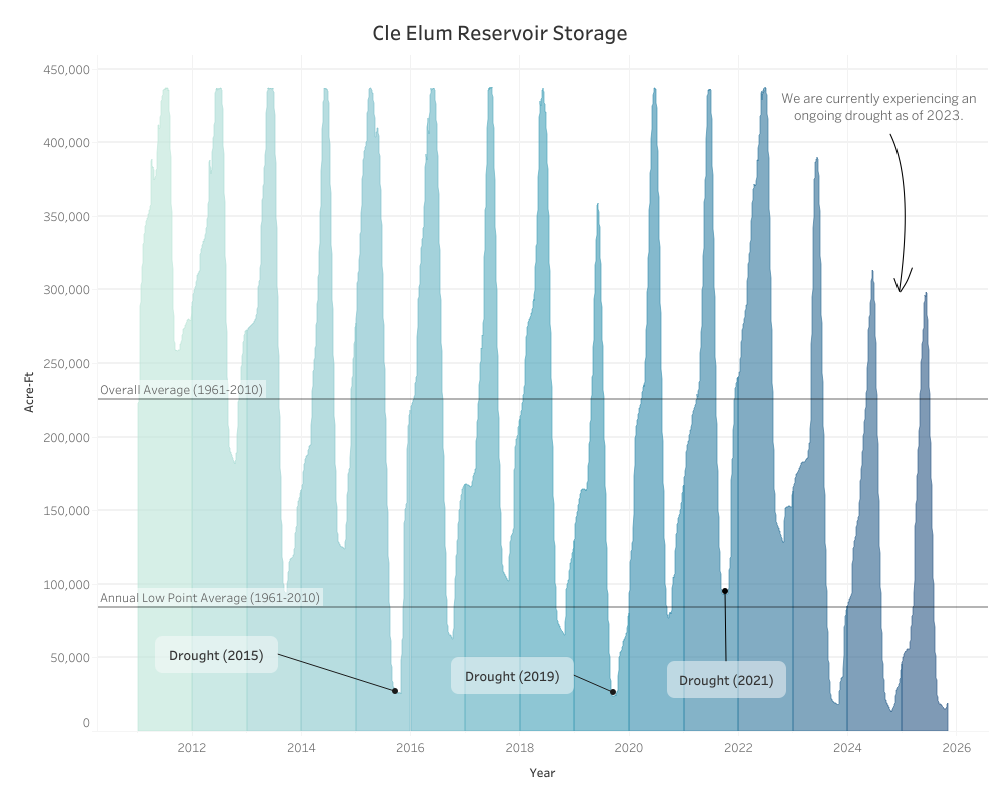

Cle Elum Reservoir levels over time – Visual: Mark Rubin/CCL

Cle Elum Reservoir levels over time – Visual: Mark Rubin/CCL

The economic stakes of Washington’s shifting water systems are substantial as well. Yakima County ranks among the nation’s most productive agricultural regions and irrigation-reliant crops and late-season water needs make farm operations particularly sensitive to the timing and reliability of summer flows.3 10 15 In some cases, farmers have begun ripping out iconic regional crops like apples and grapes due in part to the limited water availability, while others have criticized the state for not restricting water diversions sooner.16

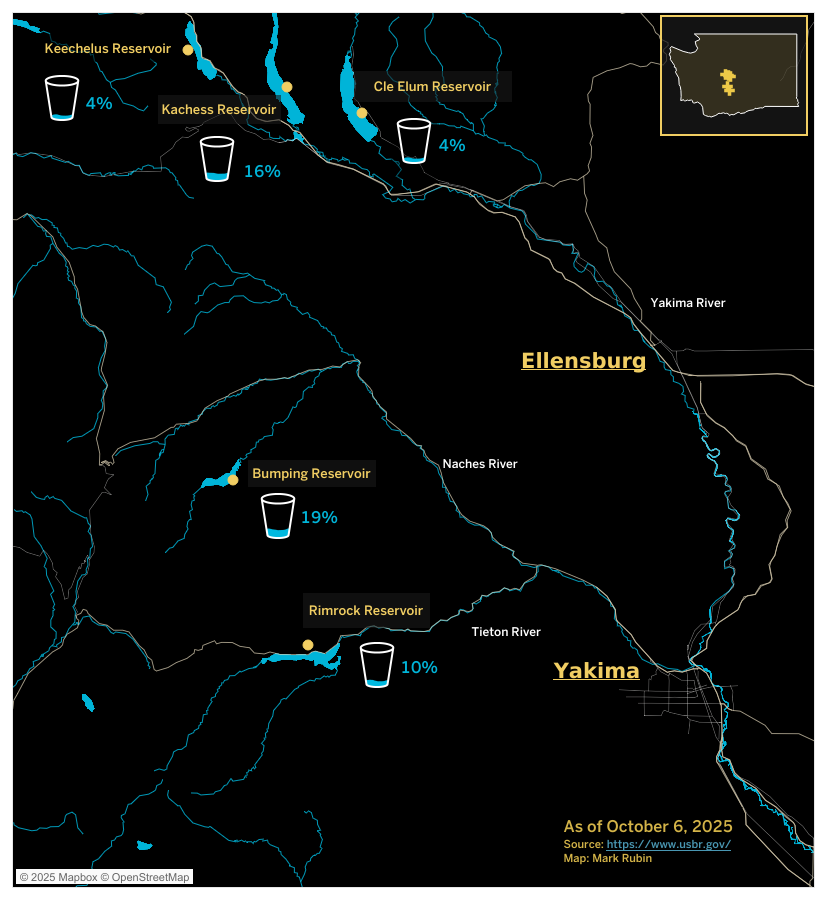

Yakima Basin Water Storage, October 6, 2025 – Visual: Mark Rubin/CCL

Yakima Basin Water Storage, October 6, 2025 – Visual: Mark Rubin/CCL

While the recent three-year drought paints a bleak picture, years of coordinated work have improved the region’s water management and provided some relief for fish and fisheries. The Yakima Basin Integrated Plan identifies improved fish passage at lower-river diversions and better flow conditions as key actions to support salmon and steelhead populations while maintaining water reliability.17 18 Current projects include design work at the Wapato and Prosser diversions to improve fish passage and reduce entrainment, the process in which fish—especially juveniles—are unintentionally drawn into irrigation canals or diversion structures where they can be injured or killed.19 20

In addition to infrastructure upgrades, water law and policy must continue to evolve to manage the Yakima Basin’s underlying hydrologic connections to better reflect ecosystem needs, tribal water rights and newer technologies. For example, scientific and legal work have together shaped how Washington manages the link between groundwater and surface water. The Center for Environmental Law & Policy (CELP) has long emphasized that hydraulic continuity (the underground connection between aquifers and streams) means that groundwater pumping can diminish flows in connected rivers, and this has helped protect flows on the Yakima.21 U.S. Geological Survey studies in the Yakima Basin confirm this relationship, showing that withdrawals from aquifers can, over time, gradually reduce streamflow.22 23 Without this critical work the current situation could be far worse. Fortunately, state and county managers have begun to treat new groundwater applications with caution, using numerical models to assess stream impacts and maintaining a moratorium on new groundwater appropriations to protect senior surface-water rights and instream flows.23

Yakima Basin Water Storage, October 6, 2025 – Visual: Mark Rubin/CCL

Yakima Basin Water Storage, October 6, 2025 – Visual: Mark Rubin/CCL

The climate context is sobering but actionable. This autumn’s water curtailment can be seen as a stress test for a water management system developed for a cooler, snowier climate. Preparing for a future with less dependable late-season water will require planning innovations: coordinating water law and policy, operational practices, habitat restoration, and demand management so they reflect the basin’s actual water availability and the needs of fish, including both treaty-protected and non-treaty fisheries. In the bigger picture, it also means advancing global climate mitigation efforts that can lessen the long-term severity of these hydrologic shifts.

References

- Washington State Department of Ecology. Dwindling water supplies force new restrictions in Yakima Basin beginning Oct. 6. October 1, 2025. Available from: https://ecology.wa.gov/about-us/who-we-are/news/2025/oct-1-dwindling-water-supplies-force-new-restrictions-in-yakima-basin-beginning-oct-6

- Washington State Department of Ecology. Water restrictions for Yakima Basin expire after Oct. 31. October 30, 2025. Available from: https://ecology.wa.gov/about-us/who-we-are/news/2025/water-restrictions-for-yakima-basin-expire-on-oct-31

- U.S. Bureau of Reclamation. Yakima River Basin Water Storage Feasibility Study. 2008. Available from: https://www.usbr.gov/pn/programs/storage_study/reports/eis/final/volume1.pdf

- Vano, J. A., et al. Climate change impacts on water management and irrigated agriculture in the Yakima River Basin, Washington, USA. Climatic Change. 2010. Available from: https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s10584-010-9856-z

- The Nature Conservancy. Allocating Water as Snowpack Declines” and “Studying Snowpack. 2019–2023. Available from: https://www.nature.org/en-us/about-us/where-we-work/united-states/washington/stories-in-washington/snowpack-declines-allocate-water/

- NOAA Fisheries. Middle Columbia River Steelhead. 2025. Available from: https://www.fisheries.noaa.gov/west-coast/endangered-species-conservation/middle-columbia-river-steelhead

- US Fish and Wildlife. Bull Trout. Available from: https://www.fws.gov/species/bull-trout-salvelinus-confluentus

- Yakama Nation Fisheries. 2023 Status and Trends Annual Report. 2023. Available from: https://yakamafish-nsn.gov/sites/default/files/projects/2023_STAR_Annual_Report_Nobleeds_10_2024_sm.pdf

- NOAA Fisheries. Middle Columbia River spring-run Chinook salmon. Available from: https://www.st.nmfs.noaa.gov/data-and-tools/Salmon_CVA/pdf/Salmon_CVA_Name_Middle_Columbia_River_spring-run_Chinook.pdf

- U.S. Geological Survey. Surface-Water-Quality Assessment of the Yakima River Basin, Washington: Spatial and Temporal Distribution of Water Quality, 1987–91 (WRI 98-4113). 1999. Available from: https://pubs.usgs.gov/publication/wri984113

- U.S. Geological Survey. Comparison of Unregulated and Regulated Streamflow for the Yakima River near Parker, Washington (OFR 82-646). 1986. Available from: https://pubs.usgs.gov/publication/ofr82646

- U.S. Geological Survey. Assessment of Eutrophication in the Lower Yakima River Basin, Washington, 2004–07 (SIR 2009-5078). 2009. Available from: https://pubs.usgs.gov/sir/2009/5078/section4.html

- Washington State Department of Ecology. Yakima River Preliminary Assessment of Temperature, Dissolved Oxygen, and pH. February 2016. Available from: https://apps.ecology.wa.gov/publications/documents/1603048.pdf

- Hatten, J. R., et al. Modeling effects of climate change on Yakima River salmonid habitats. Climatic Change. 2014. Available from: https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s10584-013-0980-4

- U.S. Department of Agriculture, National Agricultural Statistics Service (NASS). 2022 Census of Agriculture, County Profile: Yakima County, Washington. 2022. Available from: https://www.nass.usda.gov/Publications/AgCensus/2022/Online_Resources/County_Profiles/Washington/cp53077.pdf

- Seattle Times. Yakima Valley drought forces WA farmers to rip out apple trees. Nov. 16, 2025. Available from: https://www.seattletimes.com/seattle-news/climate-lab/yakima-valley-drought-forces-wa-farmers-to-rip-out-apple-trees/

- Washington State Department of Ecology. Yakima Basin Integrated Water Resource Management Plan. November 2011. Available from: https://usbr.gov/pn/programs/yrbwep/reports/DPEIS/DPEIS.pdf

- U.S. Bureau of Reclamation. Yakima River Basin Study — Resource Management Plan. April 2011. Available from: https://www.usbr.gov/watersmart/bsp/docs/finalreport/Yakima/YakimaRiverBasinStudy-ResourceMgmtPlan.pdf

- U.S. Bureau of Reclamation and Yakama Nation. Wapato Diversion: Improvements for Anadromous Fish Passage (WaterSMART Aquatic Ecosystem Restoration Projects for Fiscal Year 2023). June 1, 2023. Available from: https://www.usbr.gov/watersmart/aquatic/docs/2023/applications/YakamaNation_WapatoDiversion_508.pdf?ref=cascadepbs.org

- U.S. Department of the Interior. Biden-Harris Administration Announces More Than $51 Million to Improve Climate Resilience and Fish Passage Across the West. December 19, 2023. Available from: https://www.doi.gov/pressreleases/biden-harris-administration-announces-more-51-million-presidents-investing-america

- Center for Environmental Law & Policy (CELP). Protect Aquifers / Streamflow Protection. 2025. Available from: https://celp.org/advocacy/protecting-drinking-water-aquifers/

- U.S. Geological Survey. Groundwater in the Yakima River Basin, Washington. January 5, 2011. Available from: https://www.usgs.gov/centers/washington-water-science-center/science/groundwater-yakima-river-basin-washington

- Yakima County. Yakima Basin Ground Water Studies. Available from: https://www.yakimacounty.us/408/Yakima-Basin-Ground-Water-Studies